The face of the newspaper has changed substantially over time, and also varies widely between publications. We take for granted that modern newspapers have image-laden spreads on the front cover, including attention-grabbing headlines with a particular kind of truncated grammar. Although tabloid newspapers are often parodied for the tone and style of their front covers, and the amount of text is a strong indicator of whether the paper you’re reading is a broadsheet or tabloid, even the more ‘serious’ papers use images and headlines today.

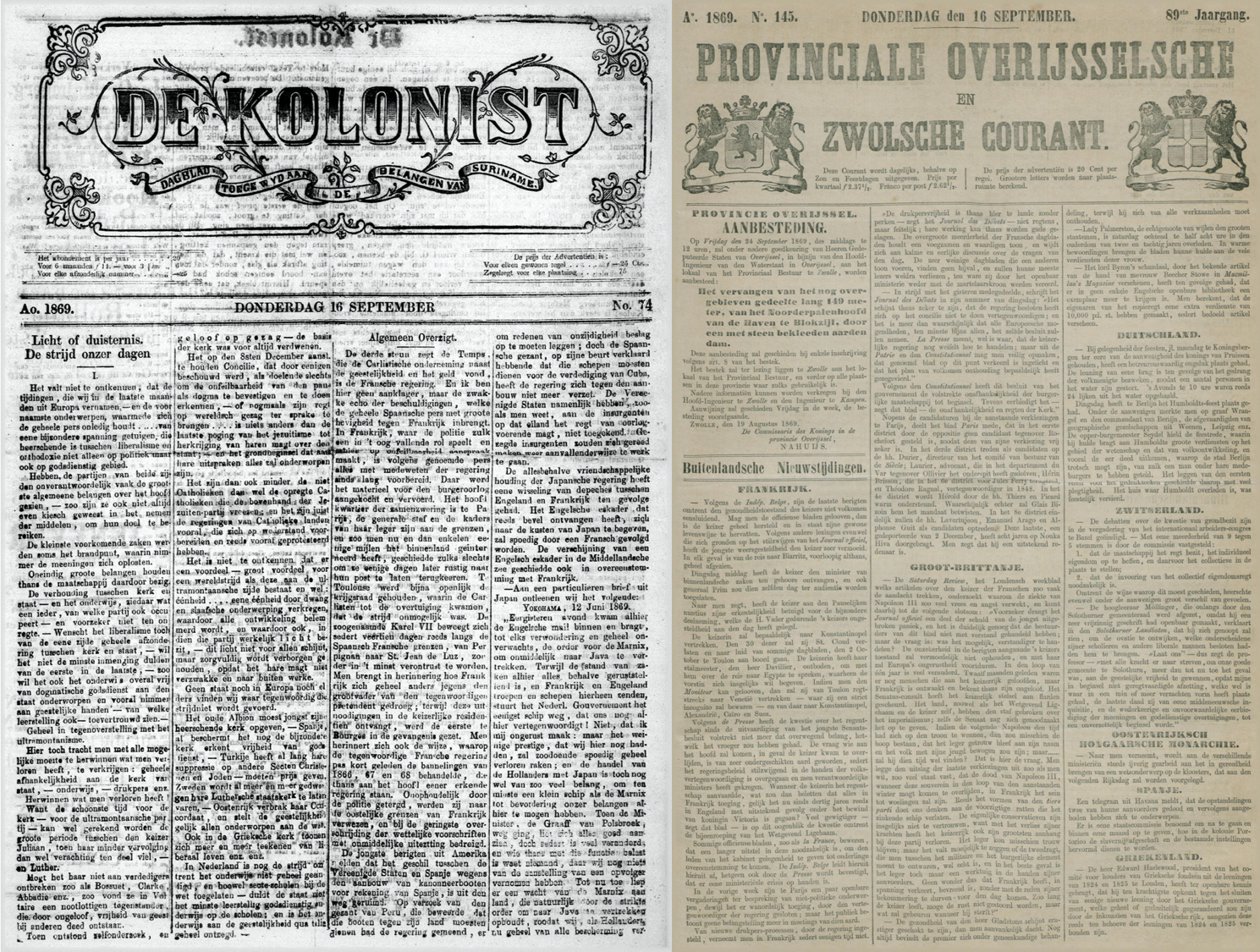

Comparison of two front pages from the same day, 16 September 1869. De Kolonist and Provinciale Overijsselsche en Zwolsche Courant. Delpher.

In the nineteenth century, this was much more controversial; in some cases, the controversy continued into the twentieth century, with The Times only introducing front-page headlines in the 1960s, stubbornly continuing with classified ads on the outer pages until then. This began as a pragmatic decision: ‘news’ within a newspaper needed to be as recent as possible, and so would generally be the last thing to be printed. To allow time to design and print the other pages, these could be done in advance. This was particularly important in the age of scissors-and-paste printing, where regional newspapers would wait for the latest news from London, and then cut and paste the articles into their own pages – sometimes literally. This reprinting was integral to the spread of news in the period, and you can use the Scissors-and-Paste-o-Meter to explore reprinting and reuse across British, colonial and American newspapers.

Copyright law in the UK did not mention newspapers directly until 1881, and even at this point there was space for quibbles about which categories should fall under the legislation; essentially, news itself was seen as something meant to be spread and shared, and was not fully recognised as a genre of writing (as opposed to just transmission of information). Internationally, the 1886 Berne Convention attempted to coordinate copyright protections around the world with some success, though the US would not join until the twentieth century.

Understanding the development of the history of the front page allows us to interrogate the nature of a specific newspaper. As taxation changes and paper becomes cheaper, the wrappers of advertisements newspapers were generally contained in thinned out and the adverts became integrated into the paper itself (though often these wrappers were not kept, and might not be reflected in the digital archive). When trying to trace reprinting, it can be difficult to trace the source; looking at page position might offer a clue. If the article is on the front page, particularly earlier in the period, it is less likely to have been reprinted. If the article goes over several pages, it is less likely to have been cut and pasted.

Looking at the evolution of the front page of a particular newspaper also throws up insightful changes in terms of margin size, number of columns, and the wealth of information in the masthead. Changes in the masthead might indicate shifts in audience, distribution, political affiliation, and ownership, as well as revealing changing tastes and technologies. Some of the interfaces of our partners facilitate this kind of analysis, such as Suomen Kansalliskirjaston digitoidut sanomalehdet and Europeana. Another project that aggregates metadata from European libraries, the Impresso Project, also has an intuitive interface for exploring front pages. No collections, however, OCR the masthead as a separate feature, instead recording the title in text form only, usually without subtitles or mottos. As OCR and OLR improve, hopefully these avenues will be easier to explore computationally, though the dense illustrations of some mastheads present a challenge for human interpretation, let alone machine learning.