The Oceanic Exchanges project aimed to bring together experienced researchers and rich data sources from around the world in order to better understand nineteenth-century patterns of news dissemination. Each of the partner institutions hosted researchers who had previously worked with at least one of the collections and these scholars worked with data providers to obtain and, where needed, licence static versions of these databases for computational research across the project. The collections were hosted on a secure server by Northeastern University, which could be consulted remotely by project partners around the world, and samples from each of these collections were examined by the team at Loughborough University to catalogue their contents, working with the providing libraries and project members to ensure this sample reflected the wider database from which it was derived.

Our first step was to create a master elements list, which provided a single entry for every possible XPath or JSON path in every collection. This included information about type of data stored, the technical definition given in the documentation, if there was one, as well as interpretive definitions, based on the research experience of project members or close examination of multiple examples within the database. The aim was to create a multi-rooted hierarchy, one that showed the position of every type of data within a given collection, by file and hierarchical placement within that file, as well as to assign to each a category, grouping metadata fields across collections. This work was not straightforward; many collections used similar schema (Dublin Core, METS, ALTO) but obtained and populated their data fields in different and often undocumented ways. Simple concepts like “title”, “publisher” and “article” became very complicated, very quickly—for example, was it a standardised title conceived by the original cataloguer, or the title as it appeared on this specific physical object, or a variant title from a particular edition? Was the information labelled “article” the media type or the editorial genre?

In the end, working with these collections required a creative and flexible interpretation of these terms and a clear understanding of the history and character of specific digital files to inform these interpretations. We began by retro-engineering the implementation of these metadata standards, starting with document type definitions (DTDs) and schema specifications and then complementing these with documentation on the cataloguing standards used. Although official documentation was often publicly available, or directly packaged with the data, we also consulted grey literature such as promotional materials or online discussions by users on the nature of the data available. Other queries were approached through experimentation—testing hypotheses on the meaning of certain fields through an examination of a large sample of records, particularly the METS/ALTO variants in multiple countries.

To clarify apparent inconsistencies within the data and with our conceptions of these terms, the project team further explored the specific histories of cataloguing, microfilming and digitising historical newspapers in these nations. By building upon previous research by the Oceanic Exchanges team, we were able to develop a robust longitudinal understanding of how the data has been augmented or repackaged by different institutions in response to technical innovations and user feedback over the past twenty years. Finally, researchers from Loughborough University, University College London, the University of Edinburgh and la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México conducted semi-structured interviews and engaged in correspondence with digitisation providers and libraries in Mexico, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, Australia and New Zealand. The earnest engagement of these providers allowed us to better understand the histories of these collections, their selection and processing of historical newspapers, and their development or adaptation of metadata for describing them.

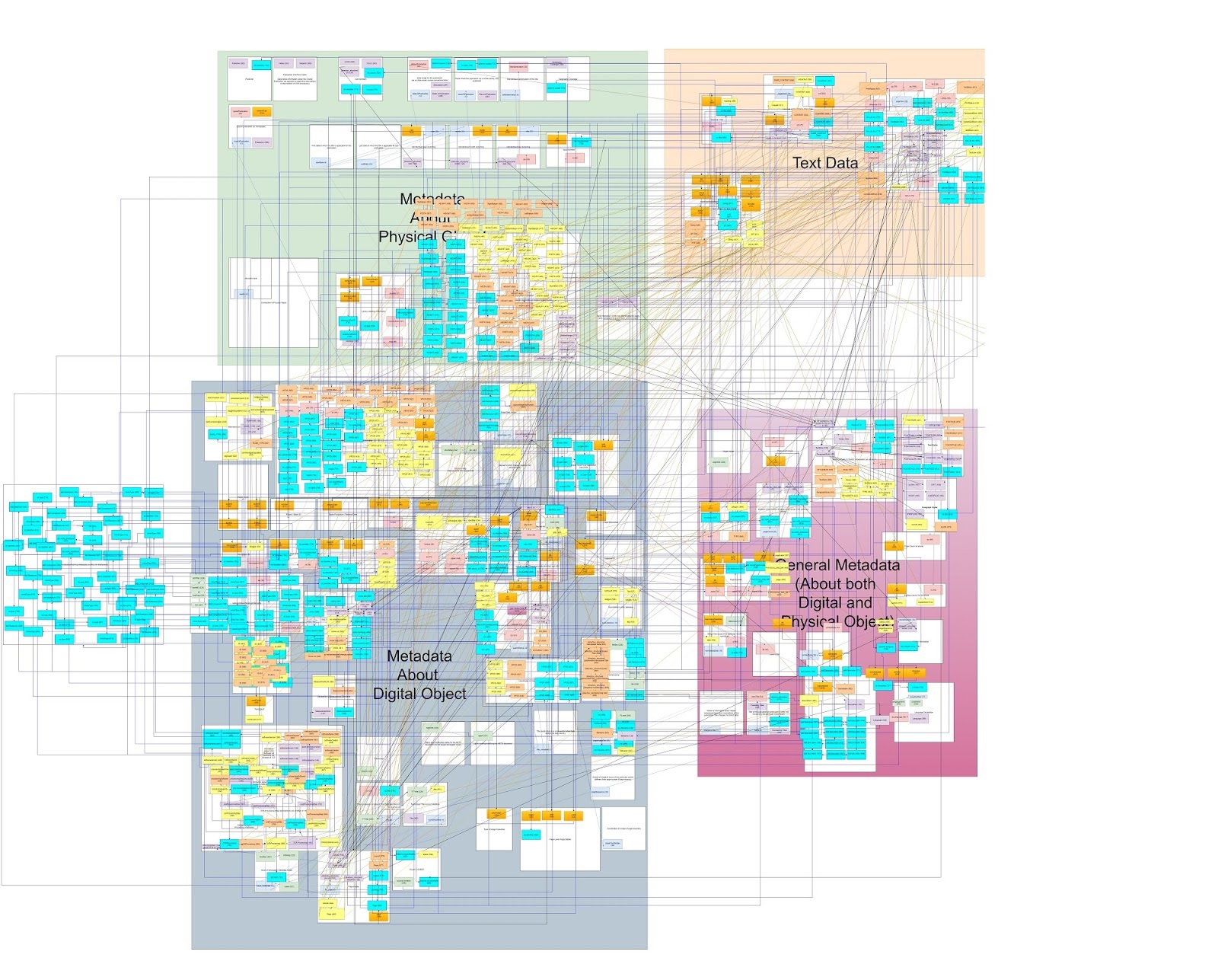

As we finalised our master list of data and metadata fields, we attempted to visually group, or map, all possible elements across all collections, using the visualisation tool draw.io; we anticipated that the majority of fields would correspond directly to similar fields in other databases and thus a visual representation would be the clearest means of conveying the information overlap between collections. However, attempts to create a single map of all possible elements and attributes, to provide provenance of internal structures while grouping object by type and subtype, raised ontological issues not only in developing hierarchies and links between the fields of the various databases but in understanding the vocabulary employed to describe elements and characteristics of the physical newspaper as well.

Fig. 1. Map of all metadata fields from our samples (each one represented by a different colour), with connecting lines showing the internal hierarchy of each, broken down by metadata of physical object, digital object, metadata pertaining to both, and text data. Unmapped blue boxes represent an overflow of repetitive administrative technical metadata.

As a result, we decided instead to create this textual ontology of the metadata fields based upon the structure of the newspaper as a physical object—a format that we hope will provide a deeper, more nuanced understanding of this ubiquitous and ambiguous medium. In the spirit of Ptolemy, this Atlas represents our attempt to provide future researchers with an initial field guide to exploring this heretofore unmappable terrain.